Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Siblings Average ratng: 4,1/5 5439 votes

Wild Bill got his man as usual but accidentally killed a friend during an 1871 Abilene shootout that played havoc with the legendary pistoleer’s mental state.

- Was Wild Bill Hickok

- Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Any Siblings

- Did Wild Bill Hickok Have A Wife

- Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Siblings Get

About 50 drunken Texas cowboys, deterred by bad weather from attending the Dickinson County Fair, accompanied gambler-cum-saloon owner Phil Coe as he toured the Abilene, Kansas, saloons and got drunker by the hour. It was the evening of October 5, 1871, toward the end of the cattle season, and most of the Texas trail hands had returned home. Many of those who remained were enjoying liquid libations with Coe as he made the rounds on Texas Street. Drunkenness per se did not violate any town ordinance, but Coe and company were armed, and Marshal Wild Bill Hickok, less than six months on his latest lawman job, had warned them against carrying firearms within city limits.

By 9 p.m. the hard-drinking crowd had reached the Alamo Saloon. A gun went off, and the diligent marshal quickly arrived on the scene, demanding to know who had fired the shot. Coe, with six-shooter in hand, said he had shot at a stray dog. To be sure, he was in no mood for a lecture from a lawman he didn’t like. Before the marshal could say another word, Coe pulled a second six-shooter and fired twice at Hickok, one shot striking the sidewalk, the other cutting through the tail of Wild Bill’s coat.

Hickok, “as quick as a thought,” according to a local newspaper, drew his own six-shooters and fired at least three times. Two of the bullets struck Coe in the stomach; the gambler would die in great agony three days later. The third bullet struck an armed man who had run between the two adversaries. Hickok, standing in the glare of kerosene lamps and surrounded by an armed and belligerent crowd, at first could not see who it was. To his horror, he soon discovered he had accidentally shot and killed his friend Mike Williams, who had served on the Abilene police force as a jailer that summer and had planned to leave town that evening to return to his ailing wife in Kansas City. A distraught Hickok (some reports say he was weeping) carried Williams into the Alamo and laid him out on a billiard table.

The gunfight turned out to be Hickok’s last. On December 13, the City Council dismissed the 34-yearold lawman and his deputies. The cattle season was over, and Abilene officials were planning to ban the cattle trade altogether, so the services of a high-priced marshal were no longer needed.

- When Hardin and his herd arrived at Abilene, Kansas, on this day in 1871, the town marshal, Wild Bill Hickok, was apparently unconcerned with prosecuting a murder that had taken place outside of.

- She was the eldest daughter of Robert and Charlotte Canary. She had five younger siblings - two brothers and three sisters. Her father moved the family from Missouri to Montana; her mother died enroute of pneumonia in 1866. Her father too died the very next year.

While in Kansas, “Wild Bill” Hickok served as a scout for General Custer and was highly thought of by the general and his wife. But Tom and Wild Bill were another matter; the two managed to get along as well as two cats hung by their tails on a clothesline. The year 1868 saw them in conflict.

Hickok never wore a badge again. Since he didn’t bother to explain himself, it’s a matter of speculation why he gave up law enforcement. Had he lost his nerve after the accidental shooting of his friend? Or was he merely being prudent because of failing eyesight and a desire to marry and settle down? These questions are open to debate, but one thing is not: James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was a changed man after the shootout at the Alamo Saloon.

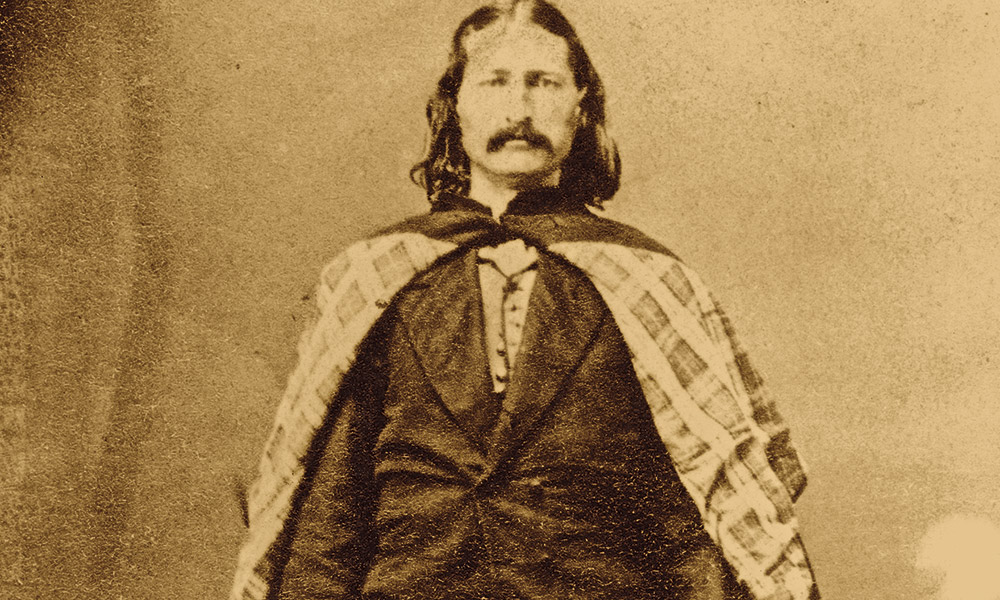

Dubbed “Wild Bill” for his zealous approach to tracking Rebel bushwhackers in Kansas and Missouri as a Union scout during the Civil War, Hickok added to his notoriety as a dead shot and proficient man-killer during various postwar stints as a government detective, scout and courier, deputy U.S. marshal, acting sheriff and town marshal. In those early years, Hickok did nothing to discourage the mythmaking. He was a great leg-puller and storyteller, whose exaggerated accounts of killing hundreds of men surfaced in an 1865 interview at Springfield, Mo., with Colonel George Ward Nichols. That account appeared in the February 1867 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, followed by one with Henry M. Stanley of the Weekly Missouri Democrat. The braggadocio caused many law-abiding citizens to look askance at Hickok and convinced him that pulling the legs of newspapermen was unwise. By 1868 he was refusing to speak to correspondents, but his legend spread anyway.

Aside from the Rebels he allegedly killed during the Civil War, Hickok is known to have fatally shot six men, two in self-defense and the others as a lawman. According to Nichols, when he asked Hickok how killing other men affected him, Wild Bill replied: “I never thought much about it. The most of the men I have killed it was one or t’other of us, and at sich times you don’t stop to think; and what’s the use after it’s all over?” Hickok told Stanley he never killed anyone without good cause, insisting that he didn’t set out to shoot anyone but that sometimes he had no choice; killing was always a last resort.

There was no doubt about Hickok’s skill with the ivory-handled .36-caliber Colt Navies slung from his waist. In a posthumous tribute, a reporter from the Chicago Tribune wrote: “The secret of Bill’s success was his ability to draw and discharge his pistols with a rapidity that was truly wonderful, and a peculiarity of his was that the two were presented and discharged simultaneously, being ‘out and off’ before the average man had time to think about it. He never seemed to take any aim, yet he never missed.”

Some gunmen were better shots than Hickok, his pal Buffalo Bill Cody once said, but few were as adept in the use of a revolver. Wild Bill cocked, aimed and fired as he drew, while most men were inclined to draw, cock and then aim and shoot, which took time.

Pistol prowess aside, Hickok’s strength of character and self-assured appearance enabled him to control others; when they saw the man, they had no reason to doubt the legend. In My Life on the Plains, George Armstrong Custer wrote that Wild Bill’s “influence among the frontiersmen was unbounded; his word was law, and many are the personal quarrels and disturbances which he has checked among his comrades by his simple announcement that ‘this has gone far enough,’” followed by the ominous comment that if they disagreed, they must “settle it with me.”

Few of Hickok’s contemporaries considered him aggressive. But if called upon, he responded without hesitation, accepting full responsibility for his actions. Where others might rely upon brothers or friends for more firepower or backup in gunfights, Hickok did not. When the shooting started, he stood alone.

Even though Hickok stopped tooting his own horn to reporters, there was no shortage of old-timers who claimed to have witnessed Wild Bill’s gunfights. Certainly his performance on the Springfield, Mo., town square on July 21, 1865, was a confrontation observers would long remember and one that would enhance his reputation. A dispute with Davis K. Tutt over a game of cards the previous evening led to a gunfight that was the epitome of the Hollywood-inspired notion of a face-to-face showdown. Some of the so-called eyewitnesses lied about that showdown (their fibs exposed when the coroner’s records were discovered after more than 100 years), but Wild Bill did indeed put a bullet into his adversary’s heart at a range of 75 yards.

Four years later in Hays City, Kan., acting Sheriff Hickok killed trigger-happy Bill Mulvey in August and then shot down saloon rowdy Samuel Strawhun the following month. Hickok’s actions on those occasions met a mixed reception, though he had apparently acted in self-defense. In assessing Hickok’s reputation on November 11, 1869, The Gazette of Delaware, Ohio, stated that he was either “heartily hated” or “more feared than loved.” Hickok lost the November election for sheriff of Ellis County, but that was in part because he was a Republican in a decidedly Democratic community. In July 1870, Hickok was back in Hays City—either for personal reasons or in his capacity as a deputy U.S. marshal— and shot two drunken 7th U.S. Cavalry troopers. It is uncertain how many cavalrymen were present, but Hickok was lucky to escape with his life.

Hickok’s Hays City days were plenty action-packed, but it was in Abilene the following year that his reputation really blossomed. Appointed town marshal, or chief of police, on April 15, 1871, he and several deputies, or constables, were expected to keep the peace and control some 5,000 Texas cowboys who came through Abilene between May and October. In general the lawmen were successful, despite the influx of gamblers, prostitutes and others eager to part the Texans from their money. When the City Council ordered Marshal Hickok to move the undesirables south of the railroad tracks, some referred to the resulting district of brothels and gambling dens as “McCoy’s Addition”—a dig at cattle baron and Mayor Joseph G. McCoy.

Hickok’s October 5 fight with the drunken Phil Coe was the kind of tragedy that was bound to happen sooner or later. Being a lawman in a cow town was dangerous work. Hickok knew this better than anyone. But he met Coe’s challenge and no doubt would have been ready to face similar challenges elsewhere had not his friend Mike Williams walked into the line of fire that night. Afterward, Hickok raged through the streets, disarming would-be troublemakers, and within an hour Abilene was like a ghost town. He insisted on paying for Mike Williams’ funeral and later visited Williams’ widow to express his regret and try to explain how the shooting happened.

Although Hickok was obviously troubled by what had occurred, few residents of Abilene blamed him, and a coroner’s inquest exonerated him. (Records of that inquest and similar records were destroyed by courthouse fires in both Abilene and Hays City.) Some newspapers botched the facts, but the accounts were generally favorable, pointing out that he “bravely did his duty.” Phil Coe, regarded as a thug by some and as a “man of good impulses” by others, got what he deserved, according to the Abilene Chronicle. Some Texans, however, disagreed and were plenty angry. Coe’s family supposedly put a $10,000 price on Hickok’s head. In November five Texans tried to ambush Hickok on a train to Topeka, but he outwitted them and continued, as one news report said, to be a “terror to evildoers.”

Although the Coe fight added to Hickok’s reputation as a gunfighter, he was no longer interested in such accolades. When offered the post of Newton, Kan., city marshal for $200 a month, Wild Bill turned it down, even though he made only $150 a month in Abilene. Had the death of Mike Williams and potential danger to other bystanders deterred him? Perhaps. Even though Hickok knew the killing was an accident, he was in no mental state to jump on another offer to wear a badge. It has been suggested the tragedy broke Hickok’s nerve, but none of his contemporaries believed that. In March 1873, a story circulated that Texans had killed Wild Bill at Fort Dodge, and Hickok finally had to dispel the rumors by writing letters to newspapers, saying he was alive. He did not sound like a man gone timid when he declared, “I never have insulted man or woman in my life, but if you knew what a wholesome regard I have for damn liars and rascals, they would be liable to keep out of my way.”

While Hickok’s nerve might have been intact, his eyesight allegedly had deteriorated and was getting progressively worse. Reports in 1874 suggest he was suffering from an eye disorder induced by the “colored fire” used when he toured with Buffalo Bill’s Combination theater troupe the prior year; later accounts mention successful treatment with “mineral drugs.” But J.W. Buel, in his 1882 book Heroes of the Plains, intimated that following a trip to the Black Hills in late 1875, Hickok sought treatment for “opthalmia” (conjunctivitis) from Kansas City physician Dr. Joshua Thorne. In her book The Buffalo Hunters, Mari Sandoz claims that in the 1930s she discovered a report by the Army surgeon at Camp Carlin, Wyoming Territory, indicating that Hickok had glaucoma and would soon go blind. That report, if it ever existed, has never been located. Camp Carlin was only a remount depot; the nearest surgeon was at Fort D.A. Russell, in Cheyenne, and its records have disclosed nothing. Nevertheless, some modern medical experts have surmised Hickok might have suffered from trachoma, an eye infection that can lead to blindness if not treated.

Whatever the state of Hickok’s vision, after the shootout at the Alamo Saloon he was circumspect about his reputation as a gunfighter. At Cheyenne in 1875, Wild Bill spoke of his burdensome reputation to Annie Tallent, one of the first white women to enter the Black Hills: “I am called a red-handed murderer, which I deny. That I have killed men I admit, but never unless in absolute self-defense, or in the performance of an official duty. I never, in all my life, took any mean advantage of an enemy. Yet understand, I never allowed a man to get the drop on me. But perhaps I may yet die with my boots on.”

By the mid-1870s the Western frontier as Hickok knew it was changing, and he decided it was time to make a new life for himself. Since his youth, he had been romantically linked with a number of women. His first love was Mary Jane, the part-Indian daughter of John Owen, who took him in as a boarder when he arrived at Monticello, Kansas Territory, in 1857. During the Civil War and on the Plains in the late 1860s, Wild Bill had several romantic affairs, including one in Ellsworth, Kan., with “Indian Annie,” who bore him a son that later died. Still, it was not until March 5, 1876, that Bill took the plunge and married. The bride was Agnes Lake Thatcher, a circus performer whose previous husband, Bill Lake, had been murdered some years before. Bill first met Agnes when her circus came to Abilene in 1871, and they were in touch for several years before the wedding.

Marriage to Agnes was meant to presage a new beginning, and Hickok needed money to support his new wife. He reportedly had made a trip to the Black Hills in 1875, and in the spring of 1876 he tried to organize an excursion of would-be gold miners to the hills from St. Louis. Discovering that others had already organized a similar expedition, Hickok put off his plans and went to Cheyenne instead. By the end of June he had joined up with his old friend Colorado Charlie Utter and was on his way to the newly founded mining camp at Deadwood Gulch.

Deadwood seemed the ideal place to make some money at the diggings (as Hickok hinted to his wife in a letter dated July 17 from Deadwood) or perhaps the first step in moving on to somewhere else. Bill told Agnes he wanted to make a home for them, and she intimated in her correspondence with his family at Troy Grove that she was eager to join him. But Hickok did far more gambling than digging, and reports published following his death that August suggested he was not a happy man. Cody, who had met Hickok en route to Deadwood in July, claimed in an interview that September that Wild Bill had said he did not expect to return from the Black Hills.

Even if Hickok’s shooting skills, vision and mental state had been in top form, they would have done him no good when a drifter named Jack McCall walked into Deadwood’s Saloon No. 10 on August 2, 1876, and shot him through the back of the head. Wild Bill was ignominiously denied the opportunity to prove whether he was still the top pistoleer in the West. And now he was dead at age 39.

Wild Bill’s niece Ethel Hickok, who was born in June 1886, almost 10 years after he was murdered, was raised on family lore that emphasized his tender side. In a number of interviews with this author over several years, Ethel said that her father, Horace Hickok, told her Wild Bill disliked his reputation as a man-killer. Ethel recalled that her mother, Martha Edwards Hickok, told her that when stories reached the family concerning his gunfights and the men he was supposed to have killed, Wild Bill’s own mother, Polly, became very upset. According to Ethel, two of the gunfighter’s brothers, Horace and Lorenzo, and his two sisters, Celinda and Lydia, all tried in vain to dispel the false stories.

But even those closest to Wild Bill doubted he ever could have settled down. Ethel said that Lorenzo Hickok, who knew his brother as well or better than anyone, once remarked that if Bill had not died in 1876, his restless spirit and adventurous streak would doubtless have kept him roaming the West. But had he done so, it would likely have been only a matter of time before some other Western ne’er-do-well or hard case took a cheap shot at the onetime lawman and still legendary pistoleer.

English writer and researcher Joseph G. Rosa is the author of many articles and books about Wild Bill Hickok. For suggested reading, try his They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok; Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth; The West of Wild Bill Hickok; and Wild Bill Hickok, Gunfighter: An Account of Hickok’s Gunfights.

Originally published in the December 2008 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.

Shutterstock

Shootouts in the Wild West are, in the popular imagination, full of stereotypes. Many movie-goers have seen Clint Eastwood as a lone drifter coming to mete out justice through the barrel of a gun or an all star team of gunslingers defending a village ravaged by bandits. The Wild West, and in particular its shootouts, are engraved into popular culture.

But are these shootouts true?

The violence of Wild West shootouts has many surprising historic kernels of truth. Where it differs is that these affairs of quick death were even more violent than imagined, and there was often little distinction between good guys and bad guys. Many of these gunfights involved brutal individuals who sometimes worked on the side of the law and sometimes did not. In most cases, drunkenness and gambling were involved. In some cases, the historical events reveal outstanding bravery, which seem to outweigh what has even been fictionalized.

Let's take a look at some of the history's most notable gunfights and gunslingers, so as to better understand the truth about Wild West gunfights.

Captain Davis slaughters a gang of desperados single-handedly

A remarkable Wild West shootout that has been largely lost to history occurred in the Sierra Nevada in 1854. According to VFW Magazine, Jonathan Davis, a former army officer, honorary captain, and veteran of the Mexican War had moved to gold-rush-era California to find his fortune. On December 19, he and two companions were outside the Sacramento area when they were suddenly barraged with bullets by 14 bandits.

One of Davis' companions was instantly killed and the other mortally wounded. Davis chose to stick it out and fight. He must have taken cover upon which he drew out his two Colt revolvers and methodically began picking off the gang one by one. Seven went down until Davis ran out of ammunition. At this point, four of the bandits came after him with knives and cutlasses. Davis, using his Bowie knife, engaged them in close combat, mortally wounding three and cutting off the nose of another. The remaining bandits fled the scene. As for Davis, he sustained two minor wounds. His clothes suffered more with multiple bullet holes.

This episode would seem to break the boundaries of fact except, according to True West Magazineand VFW Magazine,the events were corroborated by miners nearby who witnessed the whole episode. Davis reportedly said, 'I did only what hundreds of others might have done under similar circumstances.'

The gunslinger of Frisco

One Old West gunfight that seems made for the silver screen is the so-called Frisco Shootout that occurred in Lower Frisco, now Reserve, N.M., in December 1884. According to D.H. Figueredo in his book, Revolvers, Vaqueros, and Caballeros, a Texan cowboy named Charlie McCarty was terrorizing the town either by taking target practice at various buildings or harassing Mexicans in a local saloon. Either way, a local justice did not act to arrest McCarty.

At this point, the 19-year old Elfego Baca, a Mexican who bristled at the Texan's discrimination, decided he was going to stand up to McCarty. He personally arrested him. However, after doing so he was surrounded by a number of McCarty's cowboy friends. Fearing for his life, Baca shot one cowboy in the knee before fleeing to an adobe house. There he holed up as 80 cowboys besieged him in a gunfight that lasted for a day and a half, with over 4,000 bullets shot at Baca. Baca managed to kill eight and wound four before a sheriff from a neighboring town arrived and broke it up. Baca was tried for murder but acquitted after it was shown that over 400 bullets had been fired into the door of the adobe that Baca hid in. He became known as the 'man of nine lives.' He went on to serve as a United States marshal and other prominent public positions. In the 1950s, Walt Disney produced a series based on his adventures.

Wild Bill Hickok duels Davis Tutt in a quickdraw

James Butler 'Wild Bill' Hickok is synonymous with western gunslingers. One of his first duels, and the first one-on-one quickdraw duel according to Tom Clavin, author of Wild Bill, occurred in July 1865 when Hickok faced off against the gambler Davis K. Tutt in Springfield, Mo. Both men had been friends, but Hickok had fallen into Tutt's debt from gambling. They fast became enemies. According to the city of Springfield, Tutt took a gold watch from Hickok as collateral and began wearing it in public to humiliate him. Tutt rejected Hickok's efforts to negotiate for the watch.

Finally, on July 21, at about 6 p.m., Hickok found Tutt in the town square wearing his watch. Hickok holstered one of his two Colt navy pistols and said, 'Don't you come across here with that watch.' At 75 yards, both men stared at one another and turned sideways. In a few seconds, Tutt went for his gun. Hickok drew his out simultaneously. Shots rang across the square. When the smoke cleared, Tutt said, 'Boys, I'm killed.' He staggered back with a chest wound and collapsed.

This duel cemented Hickok's reputation as an icon of Old West lore.

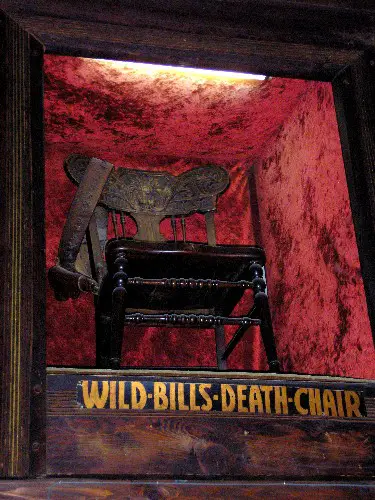

Aces and eights: Wild Bill's last hand

Wild Bill Hickok's reputation was such that according to American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales, he was hired as a deputy U.S. Marshal and served for several years. However, in 1871 his life took a downward turn when, as marshal of Abilene, Kan., he accidentally killed his deputy in a shootout. He left law enforcement and bounced around, even trying to (and failing) perform in Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. He eventually found himself in Deadwood in the Dakota territory, where he prospected for gold by day and gambled and drank at night. Invariably, Hickok would seat himself with his back to the wall. However, on the night of Aug. 2, 1876, there was only one chair available, and that seat faced toward the wall. It proved to be Hickok's undoing since a man named Jack McCall, who had badly lost to Hickok in cards the night before, went up to the veteran gunslinger and shot him in the head.

The hand Hickok was holding, two aces and two eights, was known thereafter as the 'Dead Man's Hand.'

Gettin' outta Dodge

Dodge City, Kan., has notoriety as once being a penultimate frontier town in the Old West. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it was founded in 1872 to take advantage of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe railway center for buffalo hides and later cattle coming up from Texas. It earned such a reputation of violent lawlessness that the much later saying, 'Gettin' Outta Dodge' became engraved in the American lexicon.

One of the most notorious incidents in Dodge involved a shootout at the Long Branch Saloon between former buffalo hunter Levi Richardson and 19-year old professional gambler 'Cock-eyed' Frank Loving, who had a lazy eye. There are several variations of their quarrel. According to James Reasoner in Draw: The Greatest Gunfights of the American West, both men were interested in the same dance hall girl. However, according to the Ford County Historical Society, the woman in question was actually Loving's wife. Either way, in March 1879, the two had an altercation with Richardson striking Loving. He promised to 'blow the guts out of that cock-eyed son of a bitch.'

Richardson's opportunity came on April 5, 1879. The Ford County Historical Society reports that Richardson gave his personal papers to an acquaintance and then visited the Long Branch Saloon, one of Loving's haunts. Richardson planted himself by a pot-bellied stove and waited. At about 8:30 that evening Loving came in. While reports from the witnesses vary, both men got to arguing and then drew their guns.

Frank Loving's luck runs out

Levi Richardson followed Frank Loving around the saloon, and, after some heated words, he opened fire at his enemy. Loving and Richardson ended up dodging and shooting around a billiard table at close quarters. The sheriff, whose office was close by, arrived quickly. By the time the law broke them up, they found Richardson shot through the chest and arm — he collapsed dead. Loving had miraculously suffered only an injury to his hand. No other person was injured.

According to the Ford County Historical Society, Loving was released by Dodge City authorities who viewed the Richardson murder as an act of self-defense. The Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters notes that by 1882 Loving had relocated to Trinidad, Colo., where he continued gambling. It is unclear if his wife joined him. It was there that he met former Dodge City denizen Jack Allen, a former deputy marshal and gambler. On April 16, the two came into conflict over gambling loans. A melee followed in Allen's establishment, the Imperial Saloon, with 16 shots fired and no injuries. Loving may have been blessing his good fortune the next day when he went to George Hammond's Hardware Store. However, while Loving was emptying the cylinder of his revolver, Allen burst in and shot Loving to death. The town was dubbed 'Turbulent Trinidad' in the press.

The shootout at the Oriental Saloon

Aside from Dodge City, another iconic Old West town is Tombstone, Ariz. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Tombstone was founded in 1877 by Ed Schieffelin, who was prospecting in southeast Arizona's Dragoon Mountains. Soldiers told Schieffelin that 'he'd find nothing there but his own tombstone.' But Schieffelin found silver instead, and by 1880, a town named Tombstone was booming.

Tombstone became renowned for its lawlessness. It sported 20 saloons and at least a dozen gambling dens. It was also known for sudden violence. One example of this was a shootout which, according to the Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters, occurred on Feb. 25, 1881, when Luke Short and Charles Storms got into an argument over a card game at the Oriental Saloon, with Short as the house dealer. Jeff Guinn notes in his book, The Last Gunfight, that the famous Bat Masterson, a Dodge City veteran who was also dealing in the saloon, broke up the fight. He walked the drunken Storms back to his hotel. However, Storms returned to the saloon where he found Short outside. He waved his gun at him. Short in response drew his own pistol and cooly killed Storms with a bullet in the heart. Short was cleared of any criminal charges. He and Masterson soon left Tombstone.

The violence at the Oriental was a mere prelude to the most famous shootout in Tombstone of them all at the O.K. Corral.

Trouble is brewing in Tombstone

The showdown at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Ariz., is the most emblematic of Old West gunfights. The incident, which according to National Geographic, occurred on Oct. 26, 1881, has been traditionally seen as a clear case of good guys versus bad guys. In this case, Marshal Wyatt Earp, his brothers, and friend Doc Holliday were fighting the nefarious gang of 'cowboys,' which included Ike and Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury.

After the town's silver rush, Tombstone grew quickly, and with it two feuding factions developed. The first was led by the Earps and their friend Doc Holliday, who was an ex-dentist turned professional gambler. According to the O.K. Corral Historic Complex, Earp's faction was supported by the business classes that included the mayor. The second faction, the 'cowboys,' were ranchers such as the Clantons and McLaurys, who often supplemented their living through cattle rustling. They had the support of the county sheriff, Johnny Behan. All had various interests in mining, cattle, and businesses in town. The McLaurys first collided with the Earps when the brothers tracked stolen mules to their ranch. Later, Virgil Earp, as town marshal, disarmed and arrested Ike Clanton for violating Tombstone's ordinance prohibiting carrying weapons in the town.

The shootout at the O.K. Corral

Was Wild Bill Hickok

According to National Geographic, the ordinance against firearms in Tombstone was galling to the cowboy faction since they were accustomed to freely carrying their firearms. The result was that Ike Clanton gathered a group of five cowboys, including the McLaurys, and purposefully defied the law. According to the O.K. Corral Historic Complex, a night of fighting and gambling brewed trouble on Oct. 26, 1881.

Marshal Virgil Earp asked Sheriff Johnny Behan for his help in disarming the cowboys. Behan, however, either could not or did not do it, nor could he prevent the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday from pursuing the Clanton-McLaury gang, who had planted themselves in a lot behind the Old Kindersley Corral. The two groups squared off.

It is unclear who fired first, but the fight was over in half a minute. Three of the five cowboys were dead. Of the Earps, all survived but were injured except for Wyatt Earp. Ike Clanton later accused the Earps of shooting unarmed men, but after it was shown that both sides were armed, the case was thrown out. Still, there were repercussions for the Earps. On Dec. 28, 1881, Virgil Earp was shot by unknown assailants and seriously injured. Then the next March, Morgan Earp was murdered. This set off a vendetta by Wyatt Earp and Holliday, who ended up killing four more cowboys. Earp and Holliday left for California in 1882. Behan's girlfriend, Josephine Marcus, also joined Earp in California.

Bankrobbers build a sense of community

Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Any Siblings

Sometimes in Old West shootouts whole communities got involved. By 1892 it seemed that the violence of the Old West had largely passed. However, according to the Dalton Defenders and Coffeeville Museum in Coffeyville, Kan., a gang of five consisting of Grat, Bob, and Emmet Dalton, as well as Dick Broadwell and Bill Powers, planned an audacious robbery to hold up two banks simultaneously.

On the morning of Oct. 5, 1892, the 'Dalton Gang' split up. Three entered the Condon Bank and two went to the First National Bank. At the Condon Bank, the bank robbers were told that the vault was timed and would not open until 9:30 a.m. Being that it was 9:20, they waited. This was a critical mistake, since word rustled through the town that a bank robbery was underway. Citizens rushed into Isham Hardware for guns and ammunition. In the shootout that followed, four of the Dalton Gang were killed in addition to three Coffeyville residents and a U.S. marshal. Only Emmet Dalton survived, despite sustaining 23 gunshots. Emmet, after serving 14 years in prison, received a pardon after rehabilitating himself. He became, according to the IMDB, a screenwriter in the early days of Hollywood.

Did Wild Bill Hickok Have A Wife

The Cherokee Courtroom Shootout

In the Old West, Native American tribes had their own justice systems. This did not prevent Americans from interfering when they viewed their interests at stake. In 1872, according to Tahlequah Daily Press, in the Goingsnake district in Oklahoma, a Cherokee named Zeke Proctor shot a white man named Jim Kesterson because Kesterson had abandoned his wife (Proctor's sister) and children to live with another Cherokee woman named Polly Beck. The Times Recordsays that Proctor accidentally killed Beck when she tried to intervene. Proctor was to be tried in a Cherokee court, and Kesterson fretted that he would be let off. He lobbied the American government to arrest Proctor if he was acquitted.

According to the U.S. Marshals Service, a posse of ten was organized by two deputy marshals. They headed to a schoolhouse where the trial was being heard. The Times Record noted that most of this posse was formed by Cherokees from Beck's family. The Marshals Service reports that as the posse rode into the clearing before the schoolhouse, several Cherokee emerged from the building and began shooting. However, the Cherokee account claimed that the shootings occurred inside. Eight of the posse were killed. For the Cherokee, three were killed and six wounded. The shootout was the largest single killing of U.S. marshals in American history and became known as the Goingsnake Massacre.

The Cherokee court ultimately acquitted Proctor and the U.S. government accepted the verdict.

Mysterious Dave Mather

One of the most enigmatic gunslingers of the Old West was 'Mysterious' Dave Mather. According to Same Lowe's Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in New Mexico History, Mather was born in Connecticut but by the 1870s had moved out west joining Bat Masterson. He soon earned the nickname 'Mysterious' for his silence. Sometimes Mather was an outlaw and other times a lawman. In either case he always seemed to shoot first.

Mather first came to prominence in Las Vegas, N.M., in the 1870s taking part in some illegal activities, befriending Doc Holliday. He then became a deputy U.S. marshal despite being suspected of robbing stagecoaches. He took part in multiple gunfights, according to the Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters.

Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Siblings Get

In 1883, Mather moved to Dodge City, where he got involved in politics and developed a grudge against Tom Nixon who replaced him as the city's assistant marshal. On July 18, 1884, Nixon was arrested for shooting at Mather at the Opera House where Mather ran a saloon. A few days later on July 21, while Nixon was standing at the corner by the Opera House, Mather appeared with his Colt and whispered, 'Tom. Oh, Tom.' Before Nixon could defend himself Mather shot him. Nixon collapsed, and Mather shot him three more times. Mather was acquitted of murder since, according to Age of the Gunfighter, the jury did not view Mather as the aggressor. Mather soon left Dodge City, and after a couple of more gunfights, Mysterious Dave, mysteriously vanished.